Recent efforts in the West, particularly in the United States, to legislate ‘caste’ as a protected category, similar to race, religion, and national origin, have elicited sharply divergent reactions. In academia and among human rights advocates, these measures have been celebrated as extending one of the world’s most ambitious affirmative action regimes: a modern state deploying law to correct centuries of structural injustice. Among American Hindus, however, these same instruments have been criticized as a continuation of colonial governance mechanisms: an externally originated, top-down project that treats Hindu social order as inherently pathological and in need of permanent disciplinary oversight by the state.

The divergence is not on the issue of caste discrimination per se. On this, there is near-universal agreement that it is wrong. It is about two deeper questions:

- Who is the legitimate authority to diagnose and remedy issues within Hindu society?

- Can Hindu society be trusted to reform itself, or must it be subjected to sustained coercive state intervention?

Historical Memory and Institutional Path Dependence

The British administration in the Indian subcontinent was the first sustained instance of a modern state making caste its object of knowledge and governance. From the 1870s onward, it undertook various efforts to codify a vast and diverse society. These included the decennial census, multiple ethnographic surveys, and new legal regimes such as the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Together, these measures served to transform what were previously fluid, overlapping indigenous identities (for example: kula, jati, gotra, rashtra, shreni, and sampradaya) into rigid, enumerated ‘Caste Schedules.’ These ‘Schedules’ were used for colonial recruitment and to designate separate electorates. They also fueled missionary propaganda that portrayed Hindu society as uniquely barbaric.

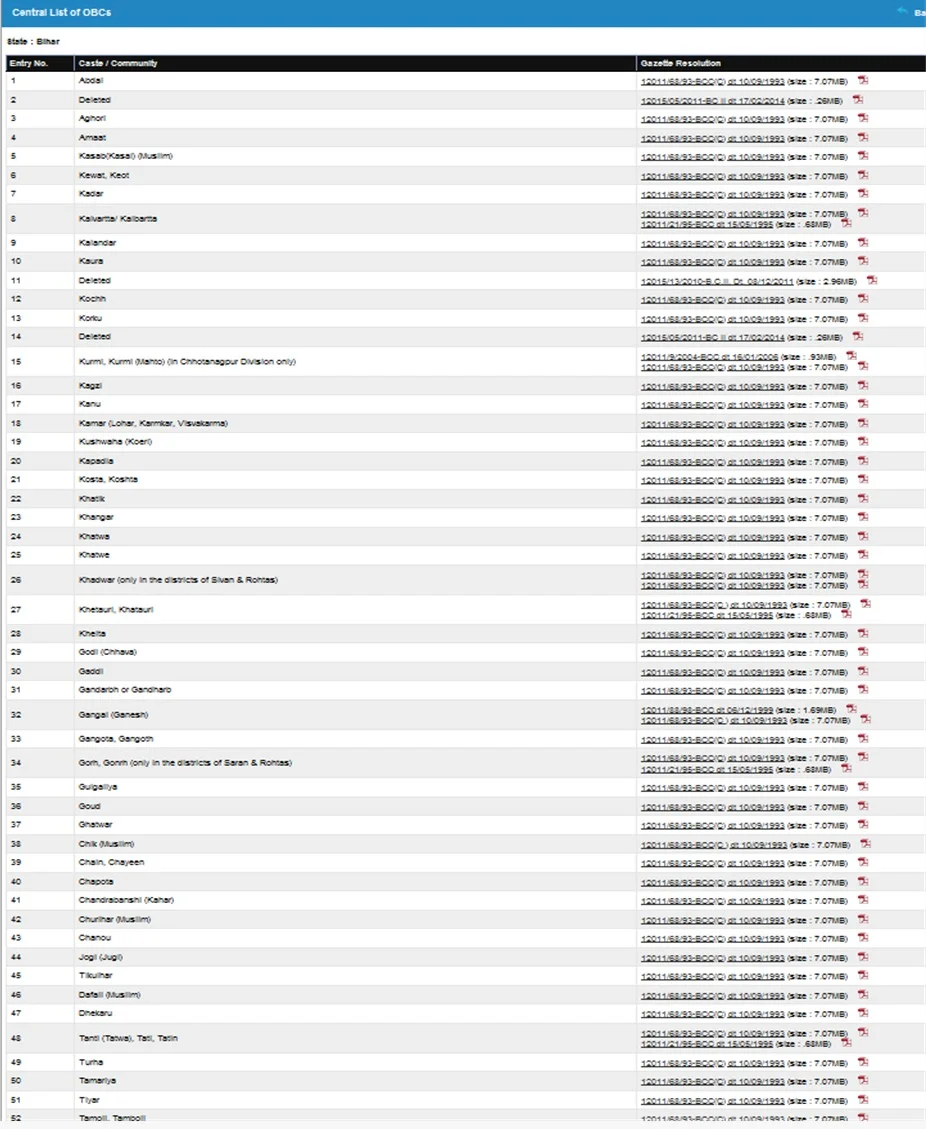

Post-Independence, in 1947, the Indian state retained and expanded this infrastructure. The British-era Caste Schedules grew to include ‘Scheduled Tribes’ and ‘Other Backward Classes’; these groups were also allotted quotas in public jobs and academic institutions. The Indian legal apparatus inherited not just administrative techniques but an entire grammar of state-society relations from the British. For Hindu society, this meant that, once again, the secular state was defining, ranking, and disciplining internal social order and, in the process, treating it as incapable of self-correction and reform.

A Typology of Attitudes Toward State and Society

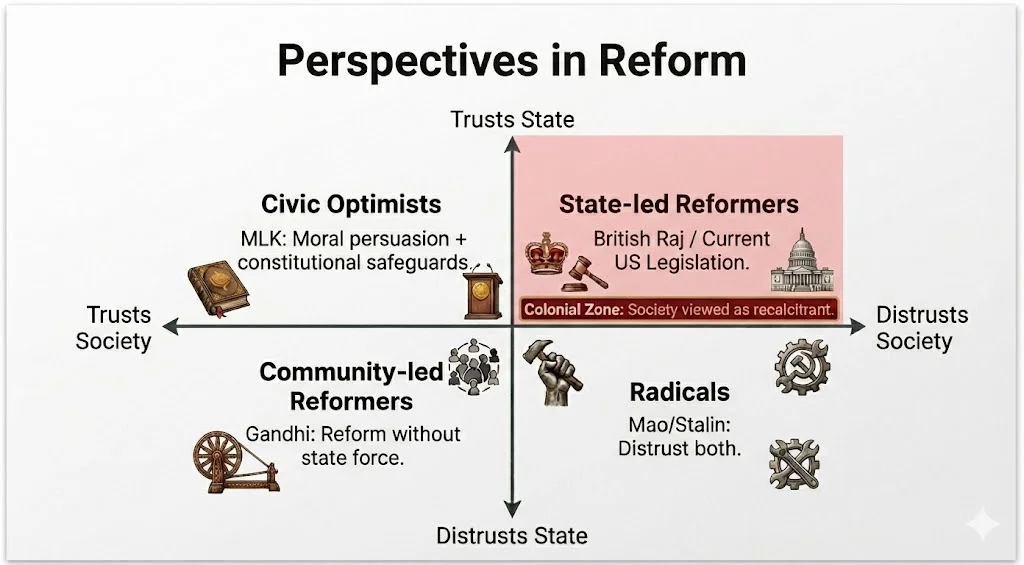

To be clear, the core issue here was not if a discriminatory system needed to be reformed. It was and remains: who can be trusted to best carry out these reforms? Some reformers and policymakers believe that when it comes to religious matters, the community must introspect and reform itself internally with minimal state intervention. Others do not trust society to reform itself, and believe that change must be enforced from the top.

Political and social actors can be mapped along two axes: their level of trust in (a) society’s capacity for internal reform and (b) the state’s ability to impose change, externally, from above or outside, as seen in the table below.

The top-right quadrant (state-led reformers) is defined by the conviction that society is too recalcitrant to reform itself and, therefore, requires state (or external) intervention. This was the operating assumption of much of the 19th and early 20th century colonial sociology of India when it came to caste-related reforms. And now, with the proposed caste legislation in the US, it seems to also have become the operating assumption for Hindu society in this part of the world.

Incentives, Evidence, and the Problem of Verification

In this establishment-led approach, the state becomes the arbiter of social identities. In India, this has meant that the post-colonial government has further solidified the problems created by the British colonial state, which froze the hierarchies of society at a point in time and hampered the natural dynamism through which groups rise and fall in socio-economic status.

Since 1947, India has built a massive bureaucratic structure to track and classify diverse groups as “castes”. This apparatus comprising commissions, officers, and surveys has been adjudicating caste certificates to individuals based on perceived statuses. Unsurprisingly, state-manufactured caste categories have yielded a complicated patchwork of distortions.

Based on official Indian census data, the total number of castes has jumped from about 4000 in 1931 to 4,000,000 and counting in 2011 in just 70 years. Each time data is collected or laws are passed, a community can be classified as “backward” or “forward”. In addition to the 1200 groups recognized at the federal level as underprivileged, India’s 28 States and eight Union Territories each have their own lists—often with conflicting versions of the status of the same group.

Complicating the issue further, especially for diaspora Hindus, caste is not an Indian issue alone. It is also prevalent in other countries across the Indian subcontinent, like Pakistan, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, all of which inherited parts of the British colonial apparatus. Each country approaches caste differently, shaped by distinct legal regimes, policy priorities, demographic compositions, and governing structures.

These complexities become even more acute when considering implementation in practice. How does one verify group identity in a diaspora context? Should one trust colonially-assigned castes in India to be a marker of societal status in the US? How will US institutions manage this interplay of identities without creating more discrimination and misinformation? Who will determine which surnames or regional origins map to which caste schedules with what standards for verification? Where do interfaith, interracial, interstate and adopted children fit in? The absence of clear criteria makes implementation virtually impossible.

Hindu community members protesting California State Bill 403, contesting the bill’s treatment of caste as an inherent religious identity rather than a colonial social practice, in April 2023. The Bill was vetoed by the Governor in October 2023.

Moreover, instead of grappling with these challenges, some institutions have already turned to caste-awareness training programs. And as is entirely expected, early evidence suggests that such efforts are counterproductive and create more harm than good. A 2023 Rutgers University study found that caste-focused diversity training increased bias against American Hindus, as participants began viewing all Hindus through a caste lens regardless of individual beliefs. Rather than reducing discrimination, the training appeared to fuel it, by painting an entire community as inherently hierarchical.

In effect, policies designed to protect against caste discrimination have instead institutionalized caste consciousness even in a society where it was not a feature. And in the process, they have marked American Hindus as uniquely requiring state oversight. There are many examples of the sort of persecution American Hindus face as a result of the growing conversation around caste and attempts to force 18th century colonial constructs onto a completely different society halfway across the world twice over.

This brings us back to the fundamental question underlying the entire debate: when the state acts on caste, is it finally healing a wounded community or is it repeating, in new linguistic garb, an old pattern of treating Hindu society as an object to be known, classified, and disciplined from above? Until that historical resonance is acknowledged, the same constitutional and legal instruments will continue to be read in two incompatible registers: as emancipatory reform by outsiders but postcolonial continuity by a substantial part of Hindu society.

Related Reading

This essay examines contemporary policy debates and the divergent reactions they provoke. For historical context on how colonial rule created the caste frameworks we’re still debating, see Part 1: “Caste is Not Ancient Hinduism but a Product of Colonialism.” For a thought experiment that reverses the colonial gaze, see Part 3: “The Harry Potter and the Ordering of Britain.”

The post Caste Legislation in the US is Not Emancipatory Reform appeared first on Coalition of Hindus of North America.

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP

Subscribe to our newsletter! Get updates on all the latest news in Virginia.

![[Aggregator] Downloaded image for imported item #134940](https://allvirginia.news/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Caste-Legislation-696x380.webp)